Rufus at Sunset Beach (or Rufus day-dreaming)

Our rat-terrier Rufus often-times goes with us for short vacations to the Atlantic beaches. North Carolina has fantastic, wide, sandy and scarcely populated beaches. Dogs are not allowed on the beach during summer season, so usually go there in the Fall and we find a lot of space and few people. Rufus enjoys enormously being at the beach, runs like a madman with other dogs in circles, plays with a tennis ball, and sniffs, sniffs and sniffs….all around this infinite place. The most he likes is to run with Zuzia, his friend and neighbor, as we often travel to the ocean with her owners. I think, for them, dogs, the beach is a synonym of freedom, especially, when there is nobody around.

Most of the time, they would care less about the local fauna, especially birds, or dolphins, not so far from the shore.

That’s despite of incredibly beautiful sites that oceanfront can offer, with stunning vistas for the morning, the day and then the sunsets.

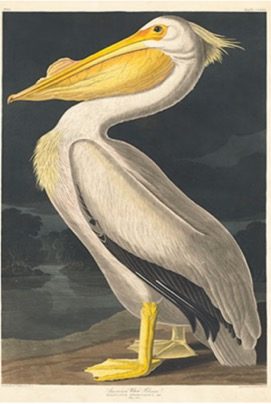

But there is one item of the world of the sea-things that definitely attracts Rufus’ attention: pelicans. When he sees them, he would stop running, perhaps sit down and quietly watch the birds majestically cruising along the shore. Like most of us.

Especially, when they cruise with their wings immobile, I would like to join them and fly with them. And I think Rufus would like that as well. And this is all my picture is about.

When I was younger I would often have a dream of me flying calmly above water, like Pelicans. As old as ancient Egyptian, dream-books (or papyruses) would explain dreams of flying as associated with the sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. I wish I had those dreams more often… these days.

All dog owners know that dogs do dream in their sleep. And as we know, they can sleep anytime, anywhere. They can as well dream about flying. That’s what I think on that matter (I know, it sounds very much like Forrest Gump).

I love watching pelicans. The dynamics of their flight is so beautiful. But also when they hunt for fish, or simply land on water. Or start. With their wings like Polish cavalry warriors of 17th century (hussars).

When I started thinking how to picture those flying pelicans, I was afraid that this was one of those kitschy subjects, like deer in the meadow, or little ducks in a pond. In fact, the marinist painters of my times avoided the subject. My uncle-painter, marinist, back in Poland, A. Suchanek, would place a sea-gull, or two, hovering over the waves, but never more than that. Neither, would his archi-rival Marian Mokwa, nor, as a matter of fact would, a super-marinist of all times, William Turner. Not a single bird in view !!! My uncle, he would paint domestic fowl, but that’s an entirely different story.

Antoni Suchanek: A view of sea, 1968ca

Antoni Suchanek, Poultry, 1958ca

If you stop thinking of sea birds, an iconic Polish xixth century painting called Storks (Bociany) immediately cames to my mind by Józef Chełmoński, one of the leading painters of so called Münich School, after Münchner Akademie der Bildenden Künste between the 1850ies and 1910ths, which was a very influential European romantic realism school, filled with Greeks, Poles (Falat, Wyczółkowski,Gottlieb, Matejko, Wierusz- Kowalski, Boznańska…) Swedes, Hungarians and other East-europeans, and a few Americans, including Harry Chase. Storkes of Chełmoński, became a quintessence of a polish country-side, as they circle in large goups on a warm afternoon, prior to departing late in the Fall toward mythical South (apparently up to Egypt).

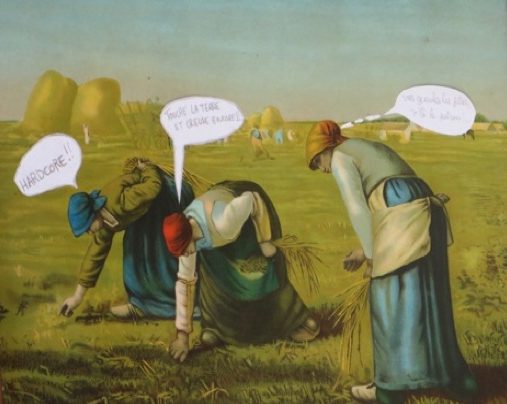

In an analogous context of Barbizan School in France there is Jean-François Millet’, Gleaners, 1857, (gleaners were peasents allowed to collect grains after the segneur’s harvest) with a barely visible flock of tiny birds. Funny socio-political coincidence regarding that painting, when I looked at it on iternet, I was struck by remembering of seeing it recently, somewhere. And it was not in a museum. I even took a photo of it, see below. It was in Impass Theo (dead-end) street in a Southern France village Pont Vieux in Dordogne, famous for an Old Bridge. The painting there, a not very thruthful (oleodruck) of a copy of the original, did not even have the birds in it. Instead, it had those three little white callouts, saying in French (“hardcore (?)”, “reach the ground and dig again”, and finally “shut up girls, the boss is coming”). Evidently, the callouts carry some political message, directed to the patrons of the little park-bench, above which it was hung across the street from a local restaurant. But Millet’s work, vastly depicting peasent life hardship, has been too early for his times. His work was repeatedly rejected by annual Paris Salon juries, and earned acid comments in the press. The same feelings brought Millet to paint “The night bird hunt”. Wild pigeon flocks gathering for the night were blinded with torch lights and clubbed down (a technique also used in 1800 rural America for wild turkey, see the Audubons memoirs). To comment on this let me quote from a posting*) by David Brett: “One of Millet’s greatest gifts was his ability to sympathize with his subjects and communicate their hardship. In this painting he has achieved the same feat, only it is the birds whose struggle is felt. As they flock toward their death, Millet painted a stunningly beautiful threnody for their luminous deaths”. His consolation could be, that his paintings were seen as inspiration by van Gogh, as he mentioned numerous times in his letters to his brother Theo, and by Claude Monet and Georges Seurat.

*)http://davidsartoftheday.blogspot.com/

J-F Millet, 1857, The Gleaners

J-F. Millet, The Gleaners, 1857

J-F. Millet, The Gleaners, 1857;

J-F. Millet, Hunting Birds at Night, 1874

So, birds were not very popular subject in 19th century French art. Not even with impressionsts. I tried to remember any other painting dedicated to birds, but I could not. Except for Audubon’s, but he had done all (American) birds. Homage to his wonderful work !

John James (Jean-Jaques) Audubon, White American and Brown Pelican, 1827-38

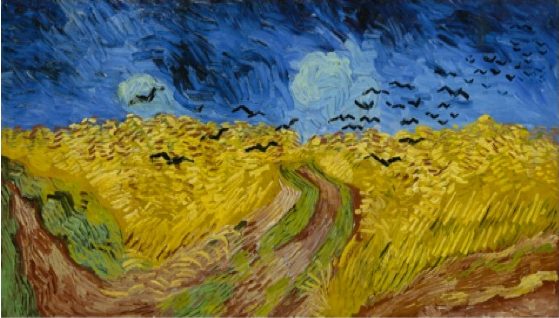

In fact, not much of any birds can be found in any of modern landscapes or so called, genre paintings (peinture de genre, fr.). I had high hopes for Peter Brueghel, van Gogh.., instead, just a few accidental birds in Bird traps (nice), and barely visible bird flock in Avercampc’s Ice Skaters. And van Gogh’s crows are just Ms in the air…

Vincent van Gogh, 1890, Wheatfield with Crows

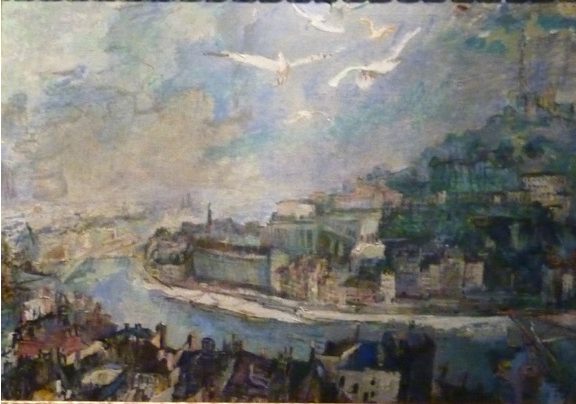

Angel-like super-birds in landscapes of Oscar Kokoschka, like in his Lyons -city landscape, shown a few years back in Phillips Gallery in Washington, DC:

Oscar Kokoschka, 1927, Lyon. City Landscape

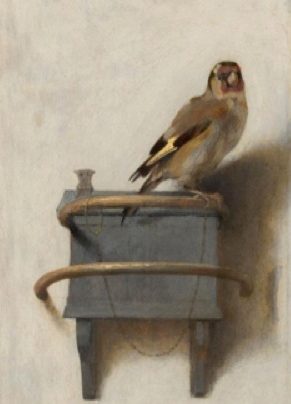

Well, there some pictures of isolated kept birds, as in now famous Fabritsius’s Goldfinch, 1654, or a Dutch Portrait of a boy with a Falcon of Willem Drost of 1650-ish.

Carel Fabritius (1622-54),The Goldfinch, 1654 ; Willem Drost (1630-1678), Portrait of a boy with a falcon

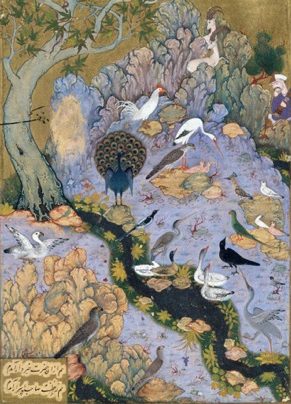

Earlier, “ornithological” studies were delivered by Flemish Frans Snyders (1579–1657) as Concert of Birds, 1629 (left, below), and in a different culture (Persian) as an illustration on a folio depicting a scene from a mystical poem, Mantiq al-tair (Language of the Birds), written by a twelfth-century Iranian, Farid al-Din ‘Attar. The birds, symbolizing individual souls in search of the simurgh (a mystical bird representing ultimate spiritual unity), are assembled in an idyllic landscape for their pilgrimage following a hoopoe bird (perched on a rock at center right). Painting by Habiballah of Sava (active ca. 1590–1610) (Right, below).

In the Renaissance painting, birds played a rather symbolic role, as in earlier medieval religious work resulting in their rather sporadic appearance, like in Duomo of Siena’s Pope Pius III (Piccolomini) Library in frescoes of Pinturicchio (I love his frescoes, they are of magnificent purity and beauty) commemorating Piccolomini’s coronation. True, birds needed to compete for room in the sky with much larger and more articulated Flying Objects, with a clear political mission, which were the Angels, as in a much later fresco of Assumption, at Santa Maria del Popolo, in Rome, both by Pinturichio.

Pinturicchio (Bernardino di Betto, detto Sordicchio) Descent of the Holy Spirit, Borgia Apartments, Vaticano, 1492- 1503, : Life of Pius, 2nd, Duomo, Siena; and Assumption, 1484-1490, Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome,

The last word is about sea in cut-outs. Many painters complained about difficulty of presenting sea waves. Turner used “rapid strokes of colour to catch the thrashing of water and the looming of cloud over the horizon. No artist has ever been able to use red the way he does to give urgency to the scene and mood to the weather”. He worked through large scale colors. And that’s in painting, and in cutouts ?

William Turner, 1842, Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth

John Marin, American modernist, 1870-1953, with his Sea, red and Cerulean Blue, 1948 was of help, as he pointed to me to a technique of small repeated forms to simulate waves. The help came also from a photography. I took this photo of a wild goose on a pond near Minneapolis, while visiting a friend on a windy sunny day.

John Marin, Sea, Red and Cerulean Blue, 1948; TH. Goose in a Minneapolis pond, 2012

I then saw the same delicate pattern formed by ocean waves. They would translate into those chain-mail structures for me.

As for the main subject of this cutouts, two final remarks I have to offer. First, check the 1505 Leonardo da Vinci’s Codice sul volo degli uccelli (with English side-to-side translation, Codex of Flying Birds): https://airandspace.si.edu/exhibitions/codex/ and you will be amazed by the acuteness of his observations as well as by the depth of his analyses. Well, a genius is a genius. Second, it appears that while Rufus and me are still at the level of dreams about flying, more active people actually fly, this way or another, check this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dcDN409ZBv

Leave a Reply