Allegory of Time

Allegory of Time

Ι have been in a sort of melancholic mood in recent months. A few friends passed away of late, which is never a good thing, and which in addition to leaving you in sorrow, reminds you an eternal truth: human beings live on average 70 something years. Clearly, there are differences between ladies and gentlemen, rich and poor, Europe, Americas, Asia, Africa… but, this way or another, life is too short. And many of us are closer to the end than to the beginning of this wonderful adventure.

That type of melancholic feelings are not something that is new, in any context. Historically, it accompanied humanity since ever, I guess. In the arts, you have plenty of expression of that feelings. Since late medieval art, one of the forms to share those feelings was something called Allegory of Time, or Allegory of Life to be more explicit, or sometimes representations of the time passing, with different tales showing it.

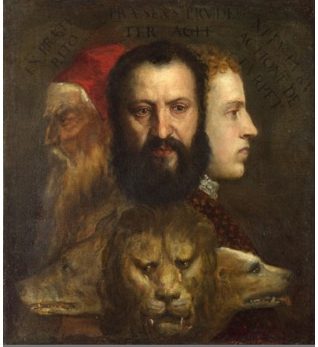

Some of the painters approached the subject very personally showing their own face in youth, maturity and old age, like Tiziano, below. However, of himself is only the old man (past), the present being the face of his son, Orazio, while future is represented by the face of his young nephew (Marco). These news come from Augusto Gentili (1955) through Stilearte.it (2018). The commentary of the title: Time guided by Prudence contains a didactic message: prudence (meant, wisdom at that time, apparently) should be inspired by experience of the past times. The suspicion is that old Tiziano was directing his didactics at his grandson, whom he wanted to keep the bottega running. Which Marco did, painting mainly in Venice, as also did Marco’s son (Tizianello). The wolf, lion and dog are representing either simply the past, present and future, or in a more sophisticated interpretation, characteristics of an artist experience: of intellectualism, of concentration and productivity, and of distraction and depression. The latter interpretation has been due to a thinker of the Tiziano’s period, Giulio Camillo.

Allegory of Time, Governed by Prudence, Tiziano Vecelli (Titian), 1565

Tiziano (or if you prefer, Titian) had another take on the subject, under the commonly used title “The three ages of man”, which has become a standard, showing, as promised, a man at childhood, maturity and old-age. Apparently, it was not Tiziano’s idea, but more commonly attributed to Giorgione….

The three ages of man, Tiziano Vecelli, (1512-1514)

The three ages of Man, Giorgione (Giorgio Barbarelli da Castelfranco): (1500-1501)

Giorgione, presumed self -portrait as David

I have a weakness for Giorgione, who unfortunately did not have a chance to live, as did Tiziano, his buddy, to experience his old age, because he died at his best years, at 32, apparently during a plague outburst in Venice. What horrible times! He is most known of The Tempest (at Accademia in Venice) and The sleeping Venus (at Dresden). By some, he is considered an inventor of a modern landscape. According to The Gossiper-in-Chief of the time, Giorgio Vasari, Giorgione (meaning Big George) was of a romantic charm, a great lover (how did Vasari know?) and a musician, “given to express in his art the sensuous and imaginative grace, touched with poetic melancholy”. But that’s just a digression.

I have a weakness for Giorgione, who unfortunately did not have a chance to live, as did Tiziano, his buddy, to experience his old age, because he died at his best years, at 32, apparently during a plague outburst in Venice. What horrible times! He is most known of The Tempest (at Accademia in Venice) and The sleeping Venus (at Dresden). By some, he is considered an inventor of a modern landscape. According to The Gossiper-in-Chief of the time, Giorgio Vasari, Giorgione (meaning Big George) was of a romantic charm, a great lover (how did Vasari know?) and a musician, “given to express in his art the sensuous and imaginative grace, touched with poetic melancholy”. But that’s just a digression.

Giorgione: The Tempest The sleeping Venus

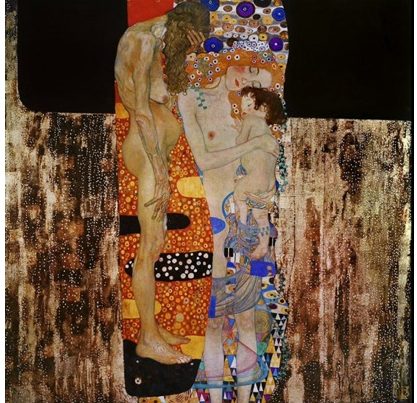

Before we go any further, let me add that it took the humanity about four hundred years to produce a work of painting entitled: “The Three Ages of Woman”, due to nobody else than Gustav Klimt, the Womanizer-in-Chief of his time (at least one that we know of), in Vienna, 1905.

A commonly used name for this picture is reductively “The mother and a child”, which obviously is intended to ignore the painter’s intention, emphasized by the title. Klimt, who was a man of a few words, has never commented on his works. Needless to say, the painting has attracted a number of comments both from the feminist and anti-feminist camp. As for my opinion in this matter, I will cite what Gombrowicz once wrote: “I am not that out of my mind, as to, in the Present Days, suppose, or not to suppose anything” (my translation of “Nie jestem ja na tyle szalonym, żebym w Dzisiejszych Czasach co mniemał albo i nie mniemał”). But I just stick to the obvious that womanhood does not certainly end with motherhood.

Gustav Klimt: The Three Ages of Woman, 1905 (Museo dell’Arte Moderna, Rome)

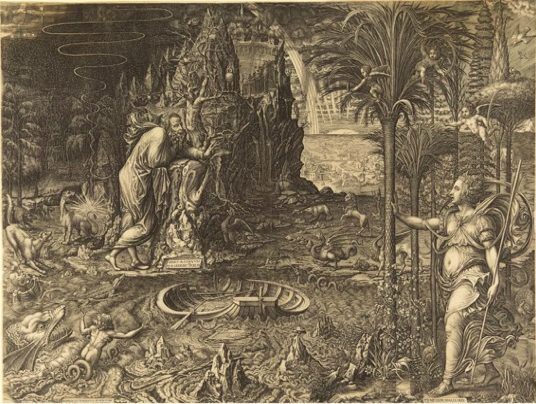

Allegory of Time (Dream of Raphael)- Giorgio Ghisi (1561): at MET

Other artists viewed the Allegory of Time, rather than the image of three-age-faces, as an accumulation of adversities of life, as did a virtuoso Italian engraver and printmaker Giorgio Ghisi (1561). Placed in a swamp full of hostile creatures, devils and who knows who, an old man begs a woman in the first plane (the fate) for help. The hope is represented in the upper right corner depicted as a bright spot with a rainbow. The subtitle of that engraving is (The dream of Raphael). This is the same title as of a much earlier (1508) engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi, who was Raphael’s buddy and co-author (with an even more confusing commentary (after Giorgione).) As many originals of both Raffaello and Giorgione are gone missing, the guess is that the engravings of Raimondi or Ghisi may be the only form through which we can have an idea of the original drawings.

Jan Brueghel, the Elder or Velvet, Allegory of Life,

The hickup continues with an oil of a much later painting by Jan Brueghel, the Elder or Velvet, son of the more famous father Pieter Brueghel and a close friend of Peter Paul Rubens, with which one cannot escape a feeling that there is a strange resemblance to Ghisi’s engraving. These guys were coping abundantly from left and right, copyrights and intellectual property were yet to be invented (but not that much: Licensing of the Press Act, 1662, and The Statute of Anne 1770, considered to be the first Copyright law, both in England).

Very commonly, Time was shown as an old man with a scythe, sometimes in company of other beings, unveiling the truth of shortness of life to unfortunate subjects, as in these two classical paintings of late renaissance mannerism period, including one of Tiepolo.

Giovan Battista Beinaschi, Allegoria del Tempo, 1680;

Time Unveiling Truth, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1758

Not everybody though had that somber approach to the passing of the time, the best counterexample of the latter is Bronzino’s work below. Seemingly, all the appropriate warnings against life follies are there, but don’t tell me that the Bronzino’s message is devoid of a dose of optimism. By the way, he could be sued in today’s USA for depicting immoral acts with a minor.

Agniolo Bronzino (or Agnolo di Cosimo di Mariano Tori)-1544-45

– Allegory of Venus and Time, or Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time, – National Gallery, London

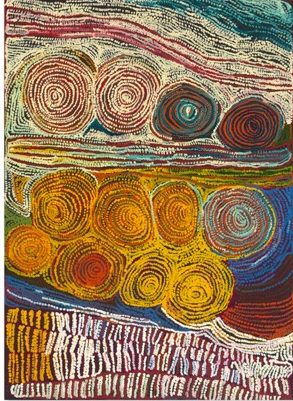

As last commentary, with respect to design of my piece, there is in it an unexpected and remote inspiration from a practically abstract work of an Australian aboriginal artist from an artist cooperative called Tjukurli Art, at Tjukurla, Western Australia shown below. I saw that piece in National Gallery of Victoria, in Melbourn and became particularly enchanted by it, as I was with a number of other art works of native Australians.

Warmurrungu, 2011, Nyarepayi Giles, Allegory of Time, 2018, TH

Tjukurla, Western Australia

Leave a Reply